What is True Cost? How did it arise? Is it a solution for a more honest and sustainable food system? Food Inspiration took a deep dive into the reports on True Cost Accounting and concluded; the philosophy is young and complex, but it has the wind in its sails. An introduction to a new way of calculating.

What is True Cost at its core?

The way companies keep their books and define their profits is incomplete, inaccurate and unsustainable. All sorts of costs during the production process affect society, people, animals and nature. They’re called hidden costs. How we currently define profits allows polluters and those who harm earth, people and animals to have a competitive advantage over those who do business in a socially responsible way. True cost ensures that the external costs that companies afflict upon society are factored into the cost price: the polluter pays.

True Cost and climate policy are closely related. The concept of True Cost can be seen as the most important instrument for measuring impact and pricing accordingly. An equitable pricing of external costs realizes climate goals. The amount of hidden costs is enormous. The FAO estimates that annual hidden environmental costs total $2,100 billion. Hidden social costs are estimated to be even higher, at $2,700 billion.

The ideology is young

The notorious report The Limits to Growth by the Club of Rome was published in 1972. It examined five major world problems in relation to each other: the growing world population, food production, industrialization, resource depletion and environmental pollution. The alarming conclusion of the report was that if the world continued to consume at the same rate, major problems would arise within a hundred years in terms of population growth and industrial production. The authors were visionaries ahead of their time. The report became the fuel for the emergence of environmental movements worldwide. And from this environmental consciousness, the concept of True Cost was born.

In 1988, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was born, the IPCC, an institute that conducts research on climate. Slowly, companies, governments, and consumers were realizing that we should treat our environment differently. The environment became one of the main themes in Al Gore's political campaign during the 2000 US presidential election. His 2006 film, An Inconvenient Truth, became a classic and triggered the world to face facts: the way we currently organize and account our economic activity has disastrous consequences for ecology.

In 2014, another important report, Food Wastage Foodprint, Full Cost Accounting was published by the United Nations FAO. The principle of Full Cost Accounting, also called True Cost Accounting, was introduced for the first time to a wider audience:

‘This document introduces a methodology that enables the full-cost accounting (FCA) of the food wastage footprint. Based on the best knowledge and techniques available, FCA measures and values in monetary terms the externality costs associated with the environmental impacts of food wastage. The FCA framework incorporates several elements: market-based valuation of the direct financial costs, non-market valuation of lost ecosystems goods and services, and well-being valuation to assess the social costs associated with natural resource degradation.’

In 2015, the FAO's second influential report soon appeared. Natural Capital Impacts on Agriculture. The study provided stakeholders with an indication of the true magnitude of the economic and natural capital costs associated with agricultural commodity production, and presented a framework that can be used to measure the net environmental benefits associated with different agricultural management practices. This second report tried to give some practical grounds to the ideas of True Cost. In what way should we measure and value these costs? This exercise is far from complete.

The ideology is developing

In recent years, there has been a flurry of reports on True Cost. An important recent report is by the Rockefeller Foundation, published in July 2021 entitled: True Cost of Food: Measuring what matters to transform the U.S food system. The report quantifies external costs for the first time leading to staggering amounts:

‘In 2019, American consumers spent an estimated $1,1 trillion on food. That price tag includes the cost of producing, processing, retailing, and wholesaling the food we buy and eat. It does not include the cost of healthcare for the millions who fall ill with diet-related diseases. Nor does $1,1 trillion include the present and future costs of the food system’s contributions to water and air pollution, reduced biodiversity, or greenhouse gas emissions, which cause climate change. Take those costs into account and it becomes clear the true cost of the U.S. food system is at least three times as big – $3,2 trillion per year.’

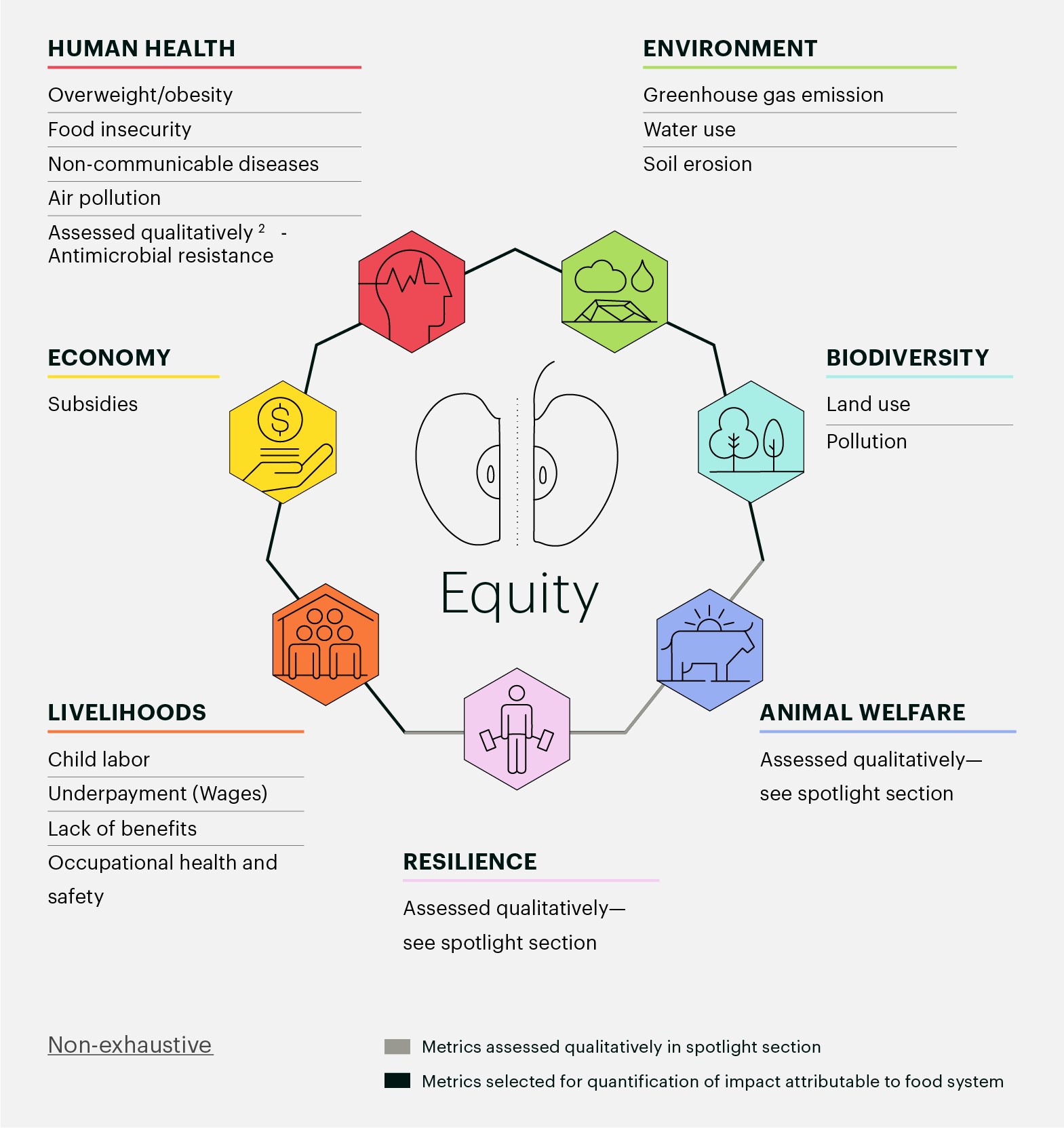

The following dimensions have been used to calculate the external costs:

Striking is the fact that this exploration is based on nine previous reports on True Cost published in recent years. In other words, the body of thought is rapidly evolving and one scientific exploration builds on another. More and more experts are willing to contribute their knowledge and reputation to the development of True Cost Accounting. The good news is that there are entrepreneurs who are using the theory, even though the accounting method is not yet perfected or widely accepted.

The ideology is complex

In fact two domains of knowledge are being developed parallel from each other, both necessary for an accurate way of calculating. On the one hand there is True Cost Accounting, the new financial framework in which external costs are factored into the cost of the product. The second domain is a holistic view of our food system. So what kind of external costs are there? What’s their impact? How are they related? Can we create a food system without negative impact on people, animals and planet and still be able to feed the world?

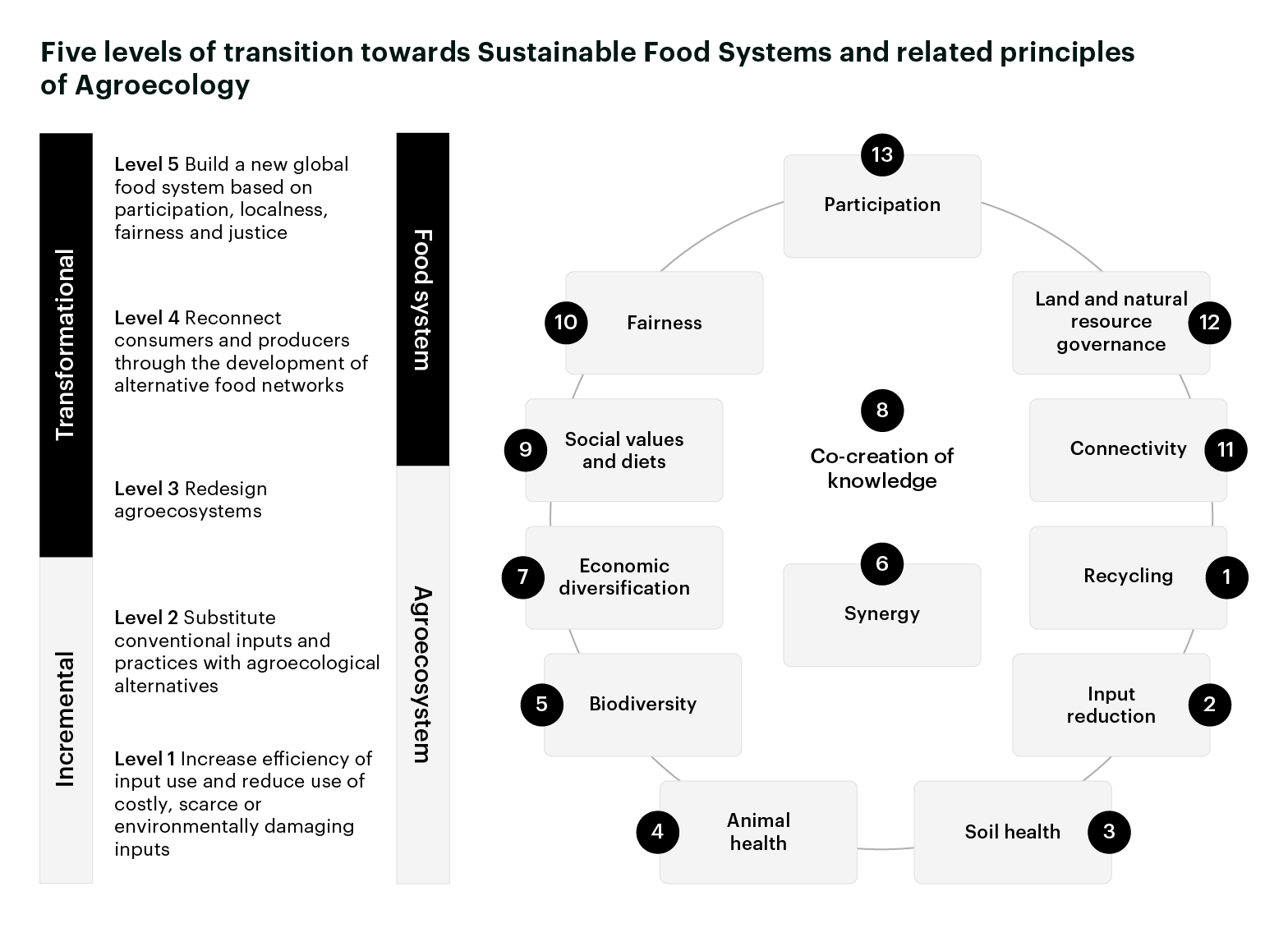

Holistic studies produce complex models. One fascinating concept comes from the HLPE report #14: Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. A group of international agrifood experts explored the impact of our food system on other areas and highlighted the importance of agroecology; agriculture that stays within planetary boundaries and still produces enough food for the world's population.

The model below shows thirteen areas that a holistic approach of the food system should take into account.

“Some people think that farmers cannot feed the world with agroecology, others contend that it is impossible to feed the world in the future without agroecology’, according to the experts. ‘Today, almost one-third of food produced for human consumption is either lost or wasted, yet different forms of malnutrition coexist in most countries. Globally, around 820 million people are still hungry, about 2 billion are overweight or obese and an estimated 2 billion people suffer from malnutrition caused by micronutrient deficiencies. FAO found that a “business as usual” scenario is likely to lead to significant undernourishment by 2050 even if gross agricultural output increases by 50 percent.”

To conclude; The good news is during recent years great progress has been made in understanding external costs within food production. The bad news: the models are still complicated. There is little time to adjust our way of calculating and to broaden existing economic profit definitions. Climate change shows that nature is becoming impatient and no longer wants to foot the bill for our irresponsible behavior. But there’s hope.

The ideology is promising

According to a growing group of supporters, using a True Cost method is a way to solve a multitude of ecological and social problems. If the true price becomes a sum of the commercial price, plus the price that nature pays for the production and distribution of a product, then companies will start to adapt. This is going to have a beneficial effect on air pollution, CO2 emissions, soil erosion, environmental degradation and climate change. Social costs will also decrease. Think about child labor, slavery, low wages, poverty, discrimination, gender inequality and other social impacts.

Prince Charles, crown prince of England is one of the champions of True Cost Accounting and organic farming. In the past, The Prince of Wales has made explicit statements about the need for True Cost Accounting tools. "We have to find a way of valuing in financial terms the increasing damage done to the earth’s life support systems by our food production. It is the economic invisibility of nature that is the root of the problem. The value of the planet’s ecosystems has not been taken into account fully and consistently in our decision making systems. We should include the true cost in the bottom line of our profit calculation rather than exclude them. Otherwise our capacity to feed the world’s rising population, on the back of an increasingly weakened ecosystem, will lead to conflict and misery on an unimaginable scale.”

The ideology is coming into its own

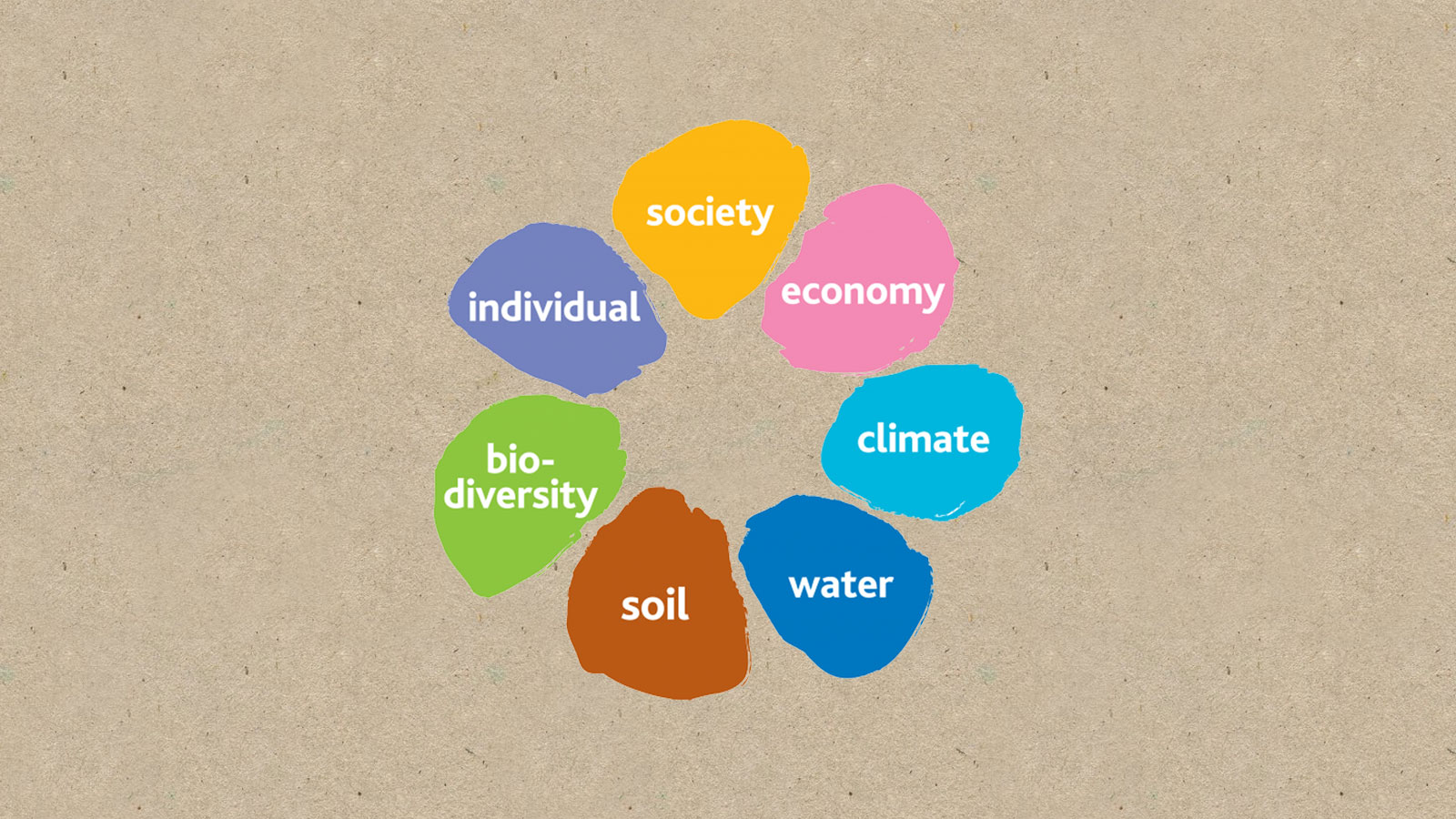

One of the pioneers in True Cost Accounting is entrepreneur Volkert Engelsman, founder of the international trading companies Eosta and Nature & more. Engelsman's brilliance is that he doesn’t just contribute to the theory buiding about True Cost, but with his fruit import company he has been putting True Cost Accounting into practice for years. To do so, he uses his sustainability flower, inspired by the United Nations SDGs. With it, he makes clear the costs and returns of the organic products he sells.

One of the conclusions is that organic apples are 19 eurocents healthier per kilo than their conventional equivalents. Why? Because the balance sheet features the impact on health, climate, water quality and soil erosion.

The sustainability flower was developed in 2009 by an international group of prominent pioneers and innovators of the organic movement. They were looking to unite ecological and social values in a single elegant model. For each aspect of the flower, performance indicators were defined on the basis of GRI Guidelines. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is an international not-for-profit organization, with a network-based structure. To enable all companies and organizations to report their economic, environmental, social and governance performance, GRI produces free Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. Accountancy firm EY contributed to the sustainability flower.

The ideology is put into practice

An example of True Cost in practice can be found in The Netherlands. At the True Price store in Amsterdam, the first of its kind in the world, they summarize the calculation like this:

True Price = retail price plus social costs plus environmental costs.

-

The retail price is the price we’re used to paying, and takes into account the economic and market forces, as well as traditional profit margins.

-

Social costs is an umbrella term including inequality in labor conditions. What would a product cost if it was produced without child or slave labor, for fair wages in safe conditions? Social costs also include racial or gender inequality, and any other societal issues standing in the way of equal rights to a good and dignified life for all.

-

Environmental costs include the toll production and distribution takes on our planet. Environmental costs include carbon emissions, air pollution, soil erosion, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, animal welfare, and other factors of the reality of climate change.

In fact, The Netherlands is a pioneering country when it comes to True Cost accounting. At the end of last year in Breukelen, according to the initiators, "the first café in the world with real prices" opened. Coffee, tea and soft drinks include the invisible costs. "The journey from farmer to plate leaves traces that inflict costs", is the underlying idea. Such as: consumption of energy, water, land and people, such as exploited workers. It is called "nature's check”.

The UK has recently taken a big step towards sustainable farming. A new impact measurement model, the Global Farm Metric, is to become the standard by which farmers and supermarkets measure and manage the impact of food production. The National Farmers Union, the British Ministry of Agriculture and four major supermarkets are supportive of this approach. The new impact model resembles Eosta’s model, the Sustainability Flower, both originating from the same international organic think tank. What's special about the British model is that non-organic farmer organizations and supermarkets are now also embracing it.

How will True Cost's ideology continue?

Volkert Engelsman is optimistic about the near future: "The impact on people and the environment is not only measured but also increasingly monetized. It's only a matter of time before shareholders will ask for more than just short-term profits. They want to know how viable a company is in the long term. Moreover, large companies have a growing talent problem: no right-thinking young person wants to work at an oil company or a bank anymore, whereas those used to be the most popular employers. Such companies lack a meaning component and are sitting on potentially stranded assets: investments in fossil energy and unsustainable agriculture."

Another fascinating vision comes from the Capitals Coalition. This NGO identifies four types of capital that need to be taken into account and monetized. For now, current economic models only consider one of the four types of capital: produced capital.

-

Natural capital: The stock of renewable and non-renewable natural resources that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people.

-

Social capital: The networks together with shared norms, values and understanding that facilitate cooperation within and among groups.

-

Human capital: The knowledge, skills, competencies and attributes embodied in individuals that contribute to improved performance and wellbeing.

-

Produced capital: The human-made goods and financial assets that are used to produce goods and services consumed by society.

Their ambition is that by 2030 the majority of business, financial institutions and governments will include the value of natural capital, social capital and human capital in their decision-making and that this will deliver a fairer, just and more sustainable world. How do they contribute? The Coalition team hosts an open, pre-competitive space for organizations to come together, share best practice and co-create solutions. The projects aim to change the math, change the conversation, change the rules and finally, change the system.

|

Selection of consulted sources:

Web

Reports

Suggestions for further reading:

|