Matt Rogers is the Founder and CEO of Mill, a waste prevention startup that helps customers turn their food scraps into farm feed. Rogers believes that technology, combined with a well-designed user experience, can effectively address food waste and create meaningful impact for people and the planet. Rogers describes his solution as the very first table-to-farm solution.

Rogers started his career at Apple. He left Apple to start Nest, building smart products for the home, including the Nest thermostat. In 2014, he joined Google and helped kickstart what's now Google Nest, departing in 2018 to start a family. Not long after, Rogers and his wife launched a small team to focus on philanthropy and climate change investment, including waste.

Food Lab Talk

A better food system starts with a vision. In his podcast series Food Lab Talk, Google's Vice President of Workplace Programs, REWS, Michiel Bakker, interviews inspiring change makers working at the forefront of our most pressing food system challenges. Each month, Food Inspiration highlights one of these visionaries. The first season of Food Lab Talk focuses on reducing loss and waste in the food system and features Matt Rogers, Founder and CEO of Mill.

Listen to the podcast episode on your favorite podcast platform »

“Waste is the second biggest product of humanity, right after concrete. One of the things that jumped out to us is that food is the biggest slice of all things in the landfill. It's the thing we dispose of the most, and about half of it is from our homes. If food waste was a country, it would be the third-largest source of emissions, right after China and the US. That blew my mind. I wasn't aware of how bad the problem was. It's a really meaningful and important climate problem that actually is tractable. Food waste is a problem that we actually can solve.”

"If food waste was a country, it would be the third-largest source of emissions"

“In 2020, in the peak of the pandemic, we were all locked in our houses. I got a call from an old colleague and friend from Google, Harry Tannenbaum. He is a really smart guy, and I respect him. He called me with this idea of creating a decentralized infrastructure for food waste, which at first sounded kind of strange. Can we take the big waste infrastructure and break it down into smaller pieces, parallel to what happened in the energy industry over the last 20 years? We used to have big power plants, and now we have solar panels and batteries and Nest thermostats and electric vehicle chargers. He asked, “How could we do something similar in waste?”

“I was intrigued. In my investment days, I noticed that waste was an important area that was often overlooked. So I thought this is worth digging into. Harry and I brought together a few advisors and friends to dig in with us. And although starting a company in 2020 was very hard, a cool and unexpected thing that happened was that everyone had time to help. Normally they would be too busy, at a conference, on holiday, but now we would cold call professors, government officials, and industry experts trying to get their advice, pick their brain on waste, and everybody would answer the phone or their emails. Everybody. That was a unique thing in 2020.”

“Looking at the problem, it's really a challenge with consumer behavior. Disposing of waste is a daily ritual that we have. No one likes trash. No one likes rats and fruit flies and the icky drippy bags and the sprint down the hall. The easiest thing to do is get it out as fast as possible. That's the system we have. But the system doesn't have to be that way. And, this is a lesson I learned from my time at Nest; if you make the right thing, the easy thing to do, it becomes the new default behavior.”

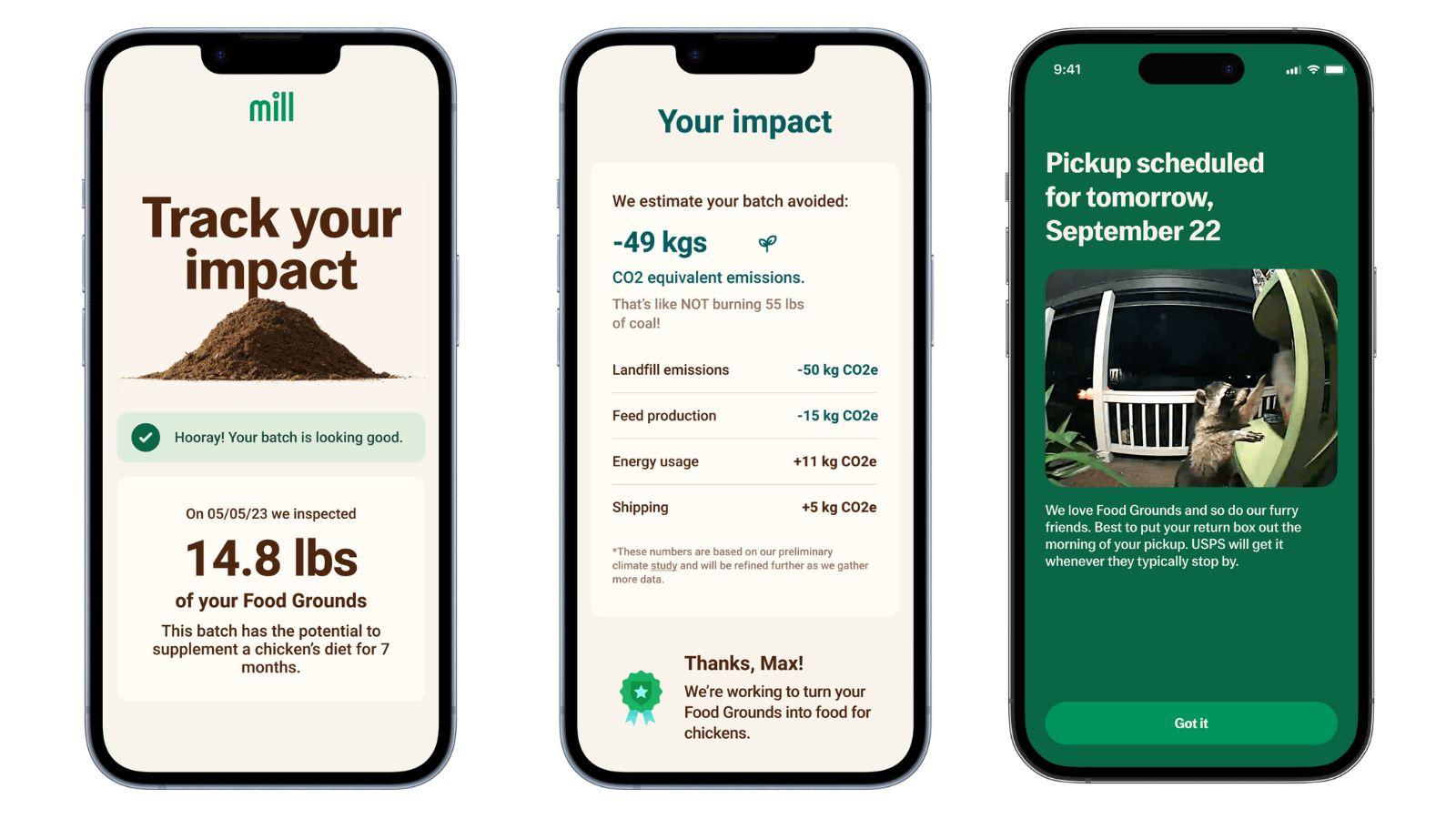

“So we built a new system. The first part of the system is a new kind of bin for your kitchen, which dries, shrinks, and de-stinks food. It takes all the food that you don't eat and makes it into what looks like coffee grounds. Actually, it's just dried food. We call them food grounds. They don't smell, they don't rot, they're shelf-stable, and they're small. As food consists of 80% water, when you take that out, it gets really small. And the same process that we use to dry it and shrink it also enables us to build a new kind of logistics network to get it back to Mill. Not in a garbage truck, but in the mail. Once or twice a month you put the food grounds in a box and through our app, you can let the post office know there's a package ready to get picked up. The box is already pre-labeled from us. You put it on your porch, they come to pick it up and it gets sent back to us, so we can get it back to farms to feed animals.”

“Obviously, the best thing to do with food waste is to eat it ourselves; the next best thing would be to feed it to an animal. So that's what we're doing. We collect all this dried food waste, we process it, pasteurize it, filter it, take out any contaminants, test it, and create an ingredient for chicken feed. There's a big farm-to-table movement today, but I think we're the first to go from your kitchen table back to the farm. The bin in itself is beautiful. It's stainless steel and white. It's about two feet tall, has a foot pedal, and a kind of wood veneer top. It is very intuitive and easy to use. You step on the pedal, it opens up, you take your dinner scraps from your cutting board, and you drop them in, and you don't think much else about it. Everything else is automatic and behind the scenes. Easy peasy.”

“Mill is not just aiming to involve eco-conscious consumers; everybody benefits. With Mill you're down one chore per day, because you no longer need to take the trash out every day. For my family of four, it takes about three weeks to fill up the Mill kitchen bin, but by taking the food component out, our normal trash doesn't fill up as quickly as before. So one, it's great to be down a chore, two, the smell is better. When you dry food, it does not smell, so it improves the kitchen experience. And that’s particularly important as a lot of us are working more from home these days. And three, it saves money. In a lot of cities around the country, consumers pay per month, based on the size of the trash cart. The bigger the bin, the more you pay. My family is saving 30 dollars a month, which is basically the cost of the whole membership for Mill.”

“Mill is not just aiming at eco-conscious consumers; everybody benefits. One: with Mill you're down one chore per day. Two: the smell is better. And three: it saves money."

“The business model for Mill works on a subscription basis. This is another lesson learned from Nest. The bin, the send-back experience, new charcoal filters, warranty, it's all bundled in a membership for about a dollar a day, $33 a month. There's no activation fee, there's no deposit. In thinking about building a circular product that's going to be good for the environment, we decided we did not want to be in the business of creating new waste. So the hardware in itself is future proof and is going to last for a really long time.”

“We've tried to design Mill so that it's easy to scale. On the manufacturing side, we've worked with a number of suppliers that are much bigger than we are, so we're sizing our manufacturing and supply chain to become a big company. On the logistics side, working with the mail is a gradual growth model. It's great to work with the USPS because they go everywhere every day. They come to your house every day, rain or shine, and those trucks mostly go back empty. So from an environmental perspective it’s great as we're not putting more trucks on the road, and from a business perspective it enables us to scale very quickly as we don't need to add more trucks or more drivers. They're already there. From a food production perspective, what's favorable is that the food grounds in your bin don’t need to undergo a big or complex transformation to turn from scraps into feed: it's mainly about filtering, sorting and sifting.”

At Mill, there is a lot of know-how about how to incentivize users to keep engaged. “One of the early lessons learned at Nest was that you have to keep people engaged and that you have to give them more than data by providing them with relevant insights into what's going on with this system and what impact they're having. So that's what we're doing.” The Mill kitchen bin has a scale built into it, so the company knows exactly how much food waste is generated. As they also collect the waste stream from their customers' doorsteps, they know exactly how much impact each individual household is having on the environment. “We’re in the process of starting to provide monthly impact reports on how much food waste you've created and how much impact you had by getting this stuff back to farms instead of landfills."

"Over time, we might start providing insights on how to waste less with benchmark data, comparing waste streams with immediate neighbors or comparable households. All with the intention of building awareness of the problem. Ultimately, if we're able to make people aware of how much food waste they're creating, they might end up going to the grocery store buying only what they need. And that's actually an enormous amount of impact and we can actually have even more systematic change. If I could dare to dream, I would love to say that we could stop sending things to landfill. Obviously, we're starting with food, and food waste is a huge issue, but what if we can end waste? No one likes waste, but we accept that it exists. What if it didn't? That would be the dream one day.”