Currently our oceans only provide a fraction of the planet's food. But farming the sea might become essential if we're to meet our ever-growing demand for sustainable and healthy food. Macroalgae, or more specific edible seaweeds, could provide a solution. We're talking about plants that grow faster than any flora on land. Sun and seawater are all it needs. It's extremely resource efficient in production and as a result – if done right – it’s as sustainable as food production can get.

Inherently sustainable

Seaweeds seem to be inherently beneficial for the environment. Researchers from Harvard recently found that coastal ecosystems (which include kelp and other sea greens) absorb more than 20 times more carbon from the atmosphere per acre than land forests. They can also be a very sustainable crop to cultivate as seaweed needs only sun and seawater. Growing seaweed requires no irrigation, no fertilizers, herbicides, feed, or arable land to grow. Cultivation can help mitigate the effects of climate change and coastal acidification by capturing and sequestering carbon. Worldwide, the seaweed value chain supports the livelihoods of approximately 6 million small-scale farmers and processors, both men and women, many of whom live in coastal communities in low- and middle-income countries (source).

A growing demand for seaweed

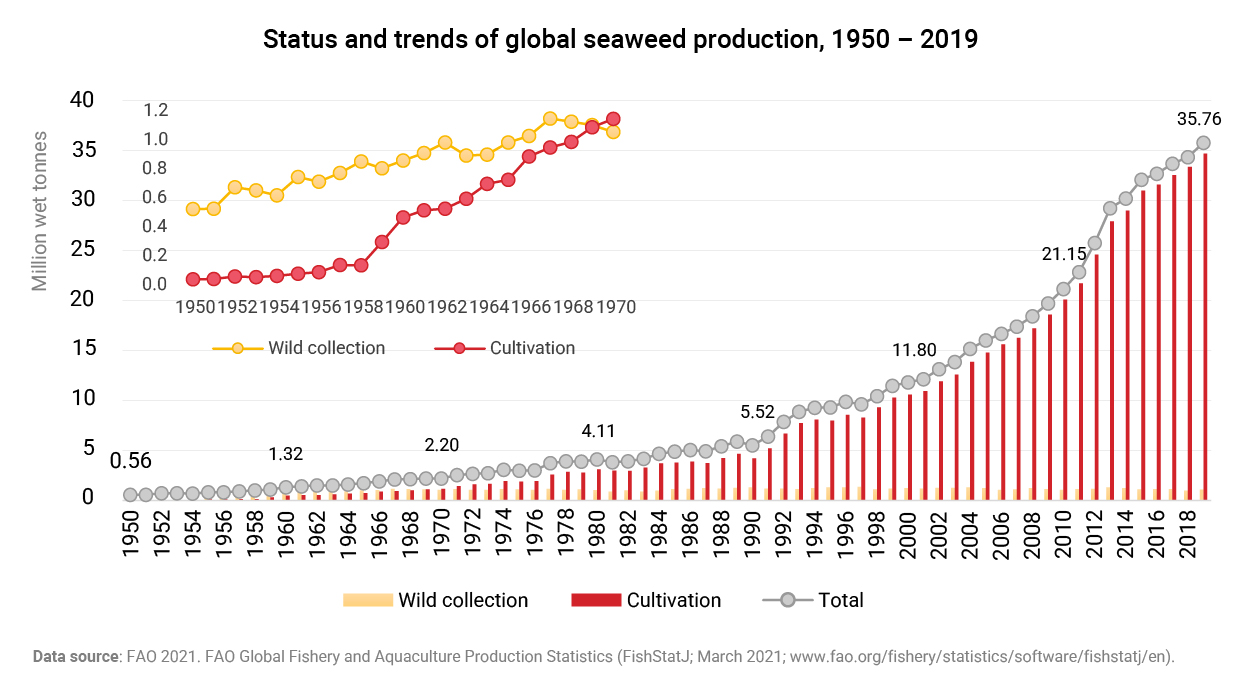

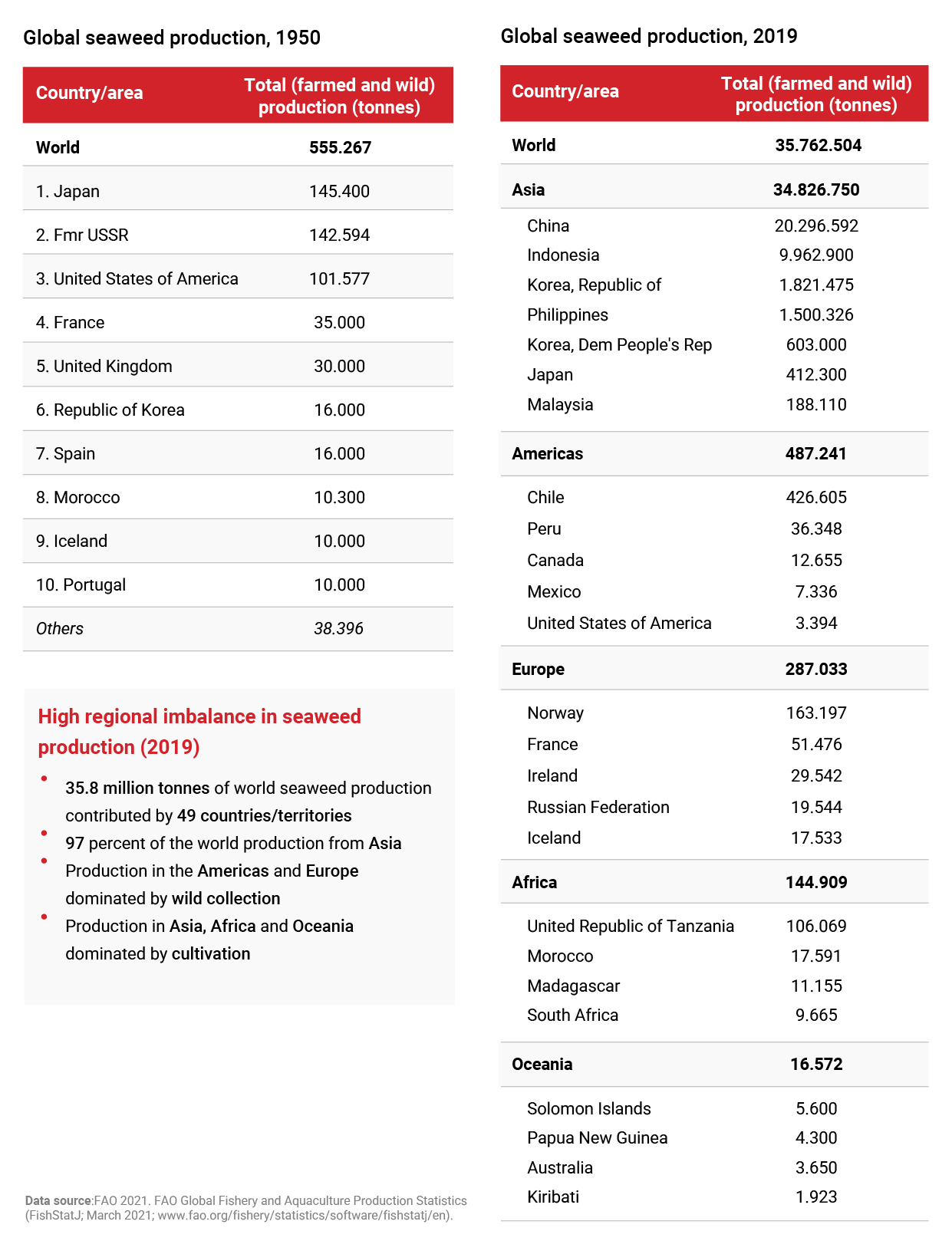

Seaweed production has grown rapidly over the past 50 years. It currently accounts for over 50% of total global marine production, equating to around 35 million tonnes. In 2019, the industry’s total value was estimated at USD 14.7 billion (source). Market projections by Global Market Insights state that the commercial seaweed industry will achieve a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 10% between 2021 and 2027 (source).

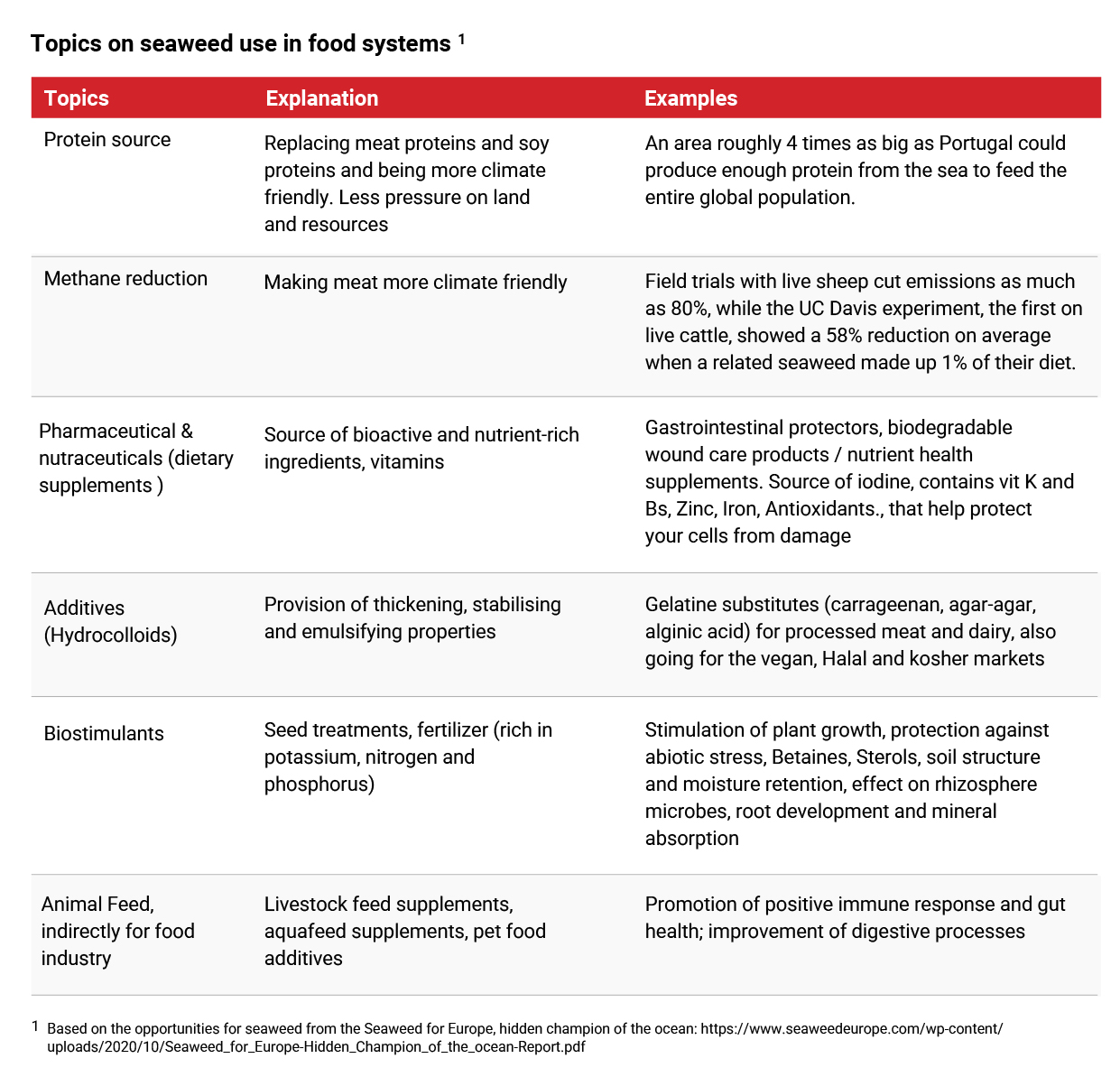

Seaweed has a wide range of ways to be utilized. It’s harvested and cultivated for human consumption (fresh or dried) and food supplements. Seaweed is also used for the extraction of hydrocolloids – such as alginate, agar and carrageenan. The food industry uses hydrocolloids – gelatinous substances – as food additives, taking advantadge of the gelling, water-retention, emulsifying and other physical properties. Seaweed is also used as feed for livestock, fertilizer, biostimulants, biofuel and raw materials for cosmetics, biopackaging, textiles.

A few statistics

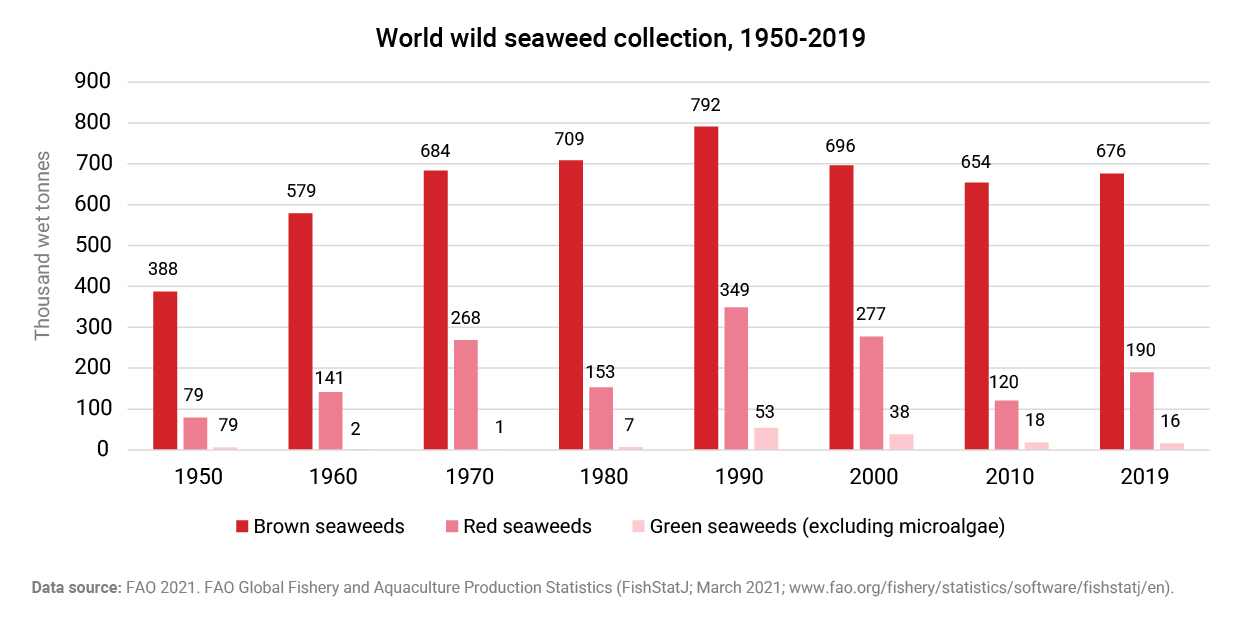

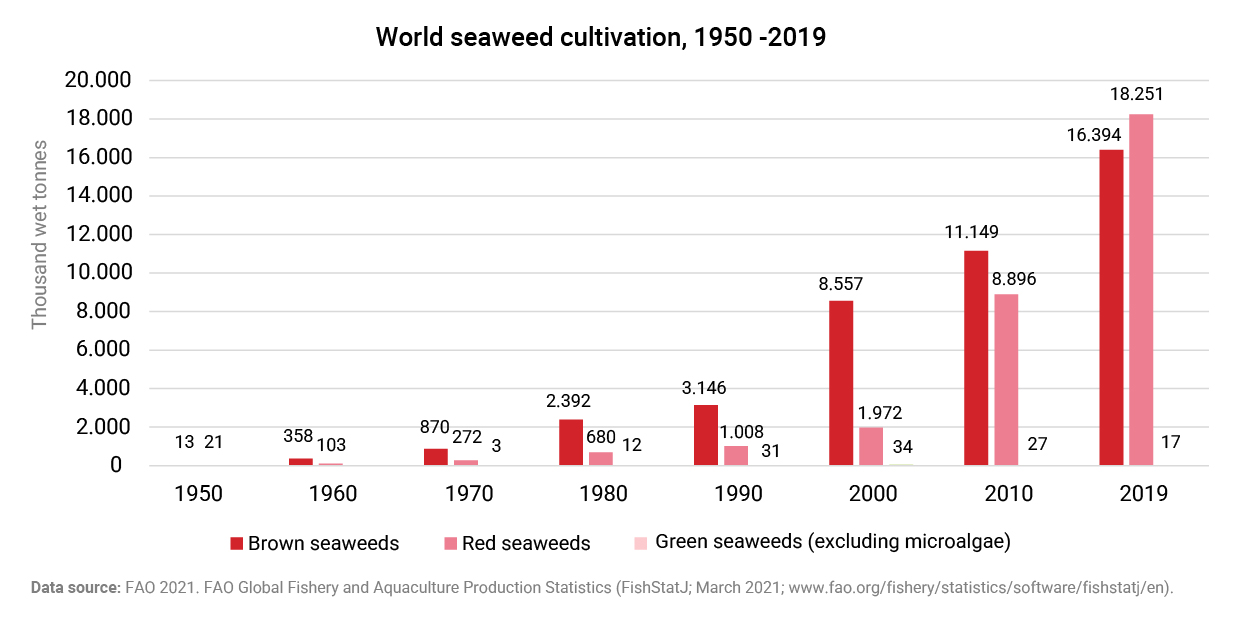

In total, there are more than 10,000 different species of seaweeds, growing in a range of different climate zones and habitats. Nonetheless, three groups of seaweed can be distinguished, based on their color: green algae, red algae and brown algae. Out of the 10,000 species, a little over 200 seaweed species are commercially relevant. In the food market, additional parameters such as taste are also taken into account. In total, approximately 145 species of seaweed are being used for food applications (FAO, 2018).

In recent years, the market for seaweed has grown substantially. World seaweed cultivation production increased by a thousandfold from 34,700 tonnes to 34.7 million tonnes between 1950 and 2019.

In 2019 Asia accounts for around 97% of the total seaweed production. In Asia production is dominated by cultivation, whereas the production in Europe and the Americas is strongly dominated by wild farming.

Over the years, wild seaweed production has been more or less stable, while cultivation has exploded, especially over the last two decades.

Note: the y-axis of both graphs have different dimensions.

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization, Global status of seaweed production, trade and utilization, May 2021

Health benefits and health risks

Seaweeds are rising in popularity because they are among the most nutrient-dense foods we can eat. In general, the mineral content in seaweeds is much higher than in plants. They are an excellent source of micronutrients, including folate, calcium, potassium, magnesium, natrium, zinc and iron. Seaweed also contains a lot of vitamins C and E and the fibers in seaweed promote gastrointestinal function. All seaweeds are an excellent source of iodine. This is important for the functioning of the thyroid gland and for memory and concentration.

As more and more people shift towards plant forward diets, seaweed has become better appreciated. Seaweed contains 5% to 30% protein and essential amino acids (source). As it also contains iron and vitamin B1 – although levels vary strongly between varieties – seaweeds are good alternatives to meat. It is not a full-fledged meat substitute because many types of seaweed do not contain vitamin B12. Sea lettuce and nori do contain B12, but Japanese research shows that a large part of this is pseudo-B12, a variant that is not absorbed by the body.

When consumed in moderation, seaweed snacks are a good source of iodine and other nutrients. However, when overconsumed, the side effects may include thyroid problems, digestive discomfort and potential exposure to radiation and heavy metals. To protect people that are sensitive to too much iodine, an upper limit for iodine intake has been established. It is 600 micrograms per day in the EU, 1000 in the US and 3000 in Japan.

WildWier harvests Dutch seaweed for chefs and consumers

Wakame, nori, and kombu are the seaweeds that you often see on the menu of Japanese or Chinese restaurants. Yet there are many more varieties of edible seaweed. Ellen Schoenmakers and Guido Krijger are the founders of the Dutch company WildWier. They supply wild-harvested seaweed from the Oosterschelde to Michelin Star chefs such as Syrco Bakker and Emile van der Staak.

Ensuring a sustainable seaweed farming sector

With ocean agriculture in its infancy, there is an opportunity to build a sustainable production system from the bottom up. We can avoid the mistakes of industrial agriculture and aquaculture, farm for the benefit of all instead of just the few, and weave economic and social justice into its DNA - all while capturing carbon, creating millions of jobs, and feeding the planet.

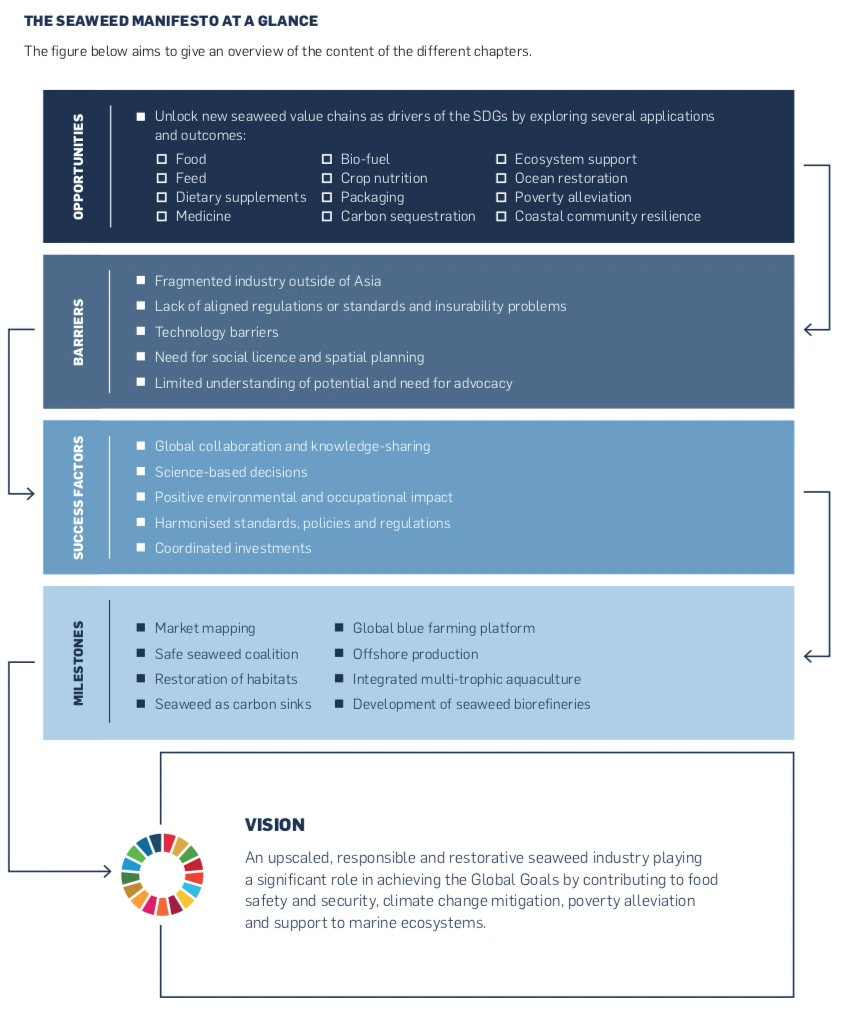

In May 2020, the Food and Agriculture Association of the United Nations (FAO) declared that we are about to enter a seaweed revolution. In that moment, the Safe Seaweed Coalition was founded, and a vision document was released: the Seaweed Manifesto. The manifesto has been initiated by Lloyd’s Register Foundation, an independent global charity that supports research, innovation and education with a mission to make the world a safer place. The work has been actively supported by the Sustainable Ocean Business Action Platform of the United Nations Global Compact. The Action Platform is taking a comprehensive view on the role of the ocean in achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

Eight recommendations

An international team of 37 seaweed scientists from across the globe has warned that the multi-billion-dollar seaweed farming industry – which has overseen rapid growth in recent years – must balance economic profitability with environment, human and organism health to ensure its long-term survival. Researchers on the international GlobalSeaweedSTAR programme, funded by UK Research and Innovation and the United Nations University Institute on Comparative Regional Integration Studies (UNU-CRIS) in November 2021 published an international policy brief, issuing a series of eight recommendations to improve the resilience and sustainability of the industry.

To quote the researchers: “The global seaweed industry faces significant challenges. For future sustainability, improvements are urgently needed in biosecurity and traceability, pest and disease identification and outbreak reporting, risk analysis to prevent transboundary spread, the establishment of high quality, disease-free seed-banks and nurseries and the conservation of genetic diversity in wild stocks."

In a press release the policy brief’s lead author and GlobalSeaweedSTAR programme leader, Prof Elizabeth Cottier-Cook, from the Scottish Association for Marine Science, said: “Improvements in biosecurity, pathogen identification and reporting systems, the establishment of seed-banks and nurseries to reduce the dependence on imports and the conservation of genetic diversity in wild stocks are urgently required if the industry is to prosper.”

“These challenges must be addressed in combination with the establishment of incentives, policies and capacity building initiatives, which protect livelihoods, are gender-responsive and increase the resilience, particularly of the small-scale farmers and processors and the wider environment, to the impacts of climate change and the globalization of this industry.”

Sustainable practices: North Sea Farmers

In recent years, several small-scale seaweed initiatives have been launched in the European coastal area, especially close to the coastline. However, large-scale cultivation of seaweed is not yet possible with the current state of cultivation techniques.

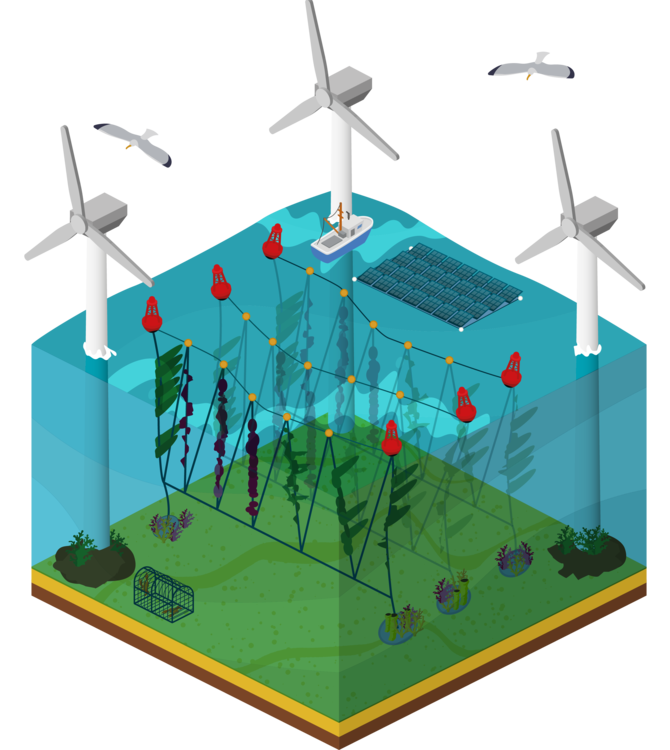

Nonprofit organization North Sea Farmers is now aiming to build the first commercial large-scale ocean farm in a wind park, starting 2023. North Sea Farmers will start with 40 hectares of seaweed farms in 2022, with the eventual goal of scaling up to 160 hectares in order to work towards a profitable farm. This is according to a study by North Sea Farmers, a trade association of companies that cultivate seaweed or market seaweed-related applications and products. The most suitable locations for sustainable seaweed farms are offshore wind farms in the North Sea.

A representation of what the ocean farm will look like in 2030 © North Sea Farmers

|

A history of eating seaweed

Consuming sea greens is hardly new. Seaweed has been eaten in Japan for at least 10,000 years, archaeologists have shown. The Celts and the Vikings also ate seaweed. Dulse seaweed (a red algae) was particularly popular for its vitamin C, which prevented scurvy. Yet seaweed was virtually nowhere on the daily menu outside of Japan. It was mainly eaten as 'emergency food' in times of famine. For example, in Ireland during the 'Great Famine' - about 1845 -1850 - the population turned to seaweed ('Irish moss') for their survival. Since then, seaweed has been considered a poor man's food that the modern Irish no longer eat. For a long time, the Bretons (inhabitants of the French region of Brittany) were the only Europeans for whom seaweed was a natural food source. Still, it wasn't until 1980 that thirteen types of seaweed were officially designated by the French government as food that can be traded and eaten by humans. As fresh seaweed wasn’t commercially available in the U.S. until Atlantic Sea Farms (formerly Ocean Approved) was founded in Maine in 2009, many Americans could historically only find it in dried forms. Now seaweeds are slowly getting their turn on more Americans’ plates. |

Written by

Written by